Second analysis of the Five-year report of the Commission on end-of-life care

Montreal, March 3, 2025 – After an earlier press release addressing the palliative care section in the “Rapport sur la situation des soins de fin de vie au Québec 2018-2023” (Report on the state of end-of-life care in Quebec 2018-2023), Living with Dignity (LWD) now focuses on the section pertaining to medical aid in dying (MAiD). This communication does not aim to summarize the Commission’s extensive work on end-of-life care but instead highlights key points that are important to the citizen network, which have not been widely covered in the media so far. The following quotes speak for themselves (quotes from the report have been translated by LWD).

Unprecedented revelation of the proportion of deaths by MAiD for each type of serious and incurable disease

“While the overall proportion of deaths by MAiD is 6.2% in 2022, this proportion varies greatly for each disease. For the most common cancers, the rates varied from 13.8% to 17.2%; for those with the most common neurological or neurodegenerative diseases (Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), the rate varied from 24.5% to 41.9%…” (p. 26).

Fear that MAiD will replace “natural death” for some seniors

“However, some people, including some Commissioners, remain concerned that MAiD may replace “natural death” for elderly people who, faced with a progressive loss of autonomy, choose to apply for MAiD rather than live in conditions they consider intolerable. As the Commission has already reminded

providers in a Communiqué, old age, even when accompanied by a significant loss of autonomy, cannot be considered a serious and incurable disease that qualifies for MAiD.” (p. 62).

Reminder that various age-related conditions, such as frailty syndrome, are not eligible for MAiD in Quebec

“The differences between Quebec and the rest of Canada could be explained by a broader interpretation of the criterion of serious and incurable illness and the inclusion of serious and incurable conditions in the other provinces. This qualifies individuals aged 90 years and over with various conditions associated with old age, such as frailty syndrome, for MAiD. However, these conditions are not considered serious and incurable diseases for eligibility for MAiD in Quebec.” (p.56).

A delay of one day or less between the request and the administration of MAiD is rare, but it does exist

“A delay of one day or less between the request for and administration of MAiD was reported in 3.6% (514/14,417) of forms documenting administration of MAiD between April 1, 2018 and March 31, 2023.” (p. 41).

During the period studied, 1,138 people withdrew their request or changed their mind

“The main reasons for non-administration of the MAiD among people who were not assessed by a physician who had agreed to take charge of their request were as follows: the people died (50.0%), they withdrew their application (22.7%) or they did not meet the eligibility requirements (13.6%).” (p. 83).

Case studies of MAiD that were deemed invalid by the Commission were very enlightening

Numerous examples on pp. 70-76 concerning “age-related frailty, natural death trajectory with several minor illnesses, morbid obesity with minor comorbidities, fibromyalgia, various symptoms without diagnosis”, etc.

Additional comments from Living with Dignity

Difference in the Definition of Slippery Slopes in

MAiD

In the report, the Commission presents its definition of the term slippery slope: “without changing the eligibility criteria in the law, (an) increasingly liberal interpretation” allowing MAiD for individuals who would not have been eligible to receive it in the first place (p. 61).

Our definition of slippery slopes also encompasses the legislative changes that have led to MAiD “no longer being exceptional care” (p. 54). In this sense, it echoes the findings expressed by several guests in Episode 4 of ICI Radio-Canada‘s La mort libre podcast, “Les pentes glissantes de l’aide médicale à mourir” (The slippery slopes of medical aid in dying).

One year after an International meeting on end-of-life issues was held in Paris, LWD is still observing slippery slopes in each of the jurisdictions that have opened the way to one form or another, of euthanasia or assisted suicide. Whether one is for or against this gesture, which some present as an “individual right”, it is never without consequences for the family, caregivers and those forced to consider it.

LWD deplores the exponential increase in access to MAiD over the period studied (an average annual increase of 41%). This increase is not comparable to the rises observed elsewhere in the world.

Socio-demographic

and socio-economic data to be studied in greater depth

Since its 5th Annual Report on Medical Aid in Dying in Canada, 2023, Health Canada has provided more socio-demographic data (e.g., p. 57 “A total of 9,619 people of the 15,343 who received MAiD responded to this question, the vast majority of whom (95.8%) identified as Caucasian (White).”).

The Commission is quick to address the indigenous and socio-cultural issue: “In the territories of indigenous communities, there are virtually no requests for MAiD, and none are reported by establishments in these regions. The same is true of other socio-cultural communities in certain territories.” (p.109).

It would be interesting to find out more about the reasons behind this difference in choice.

The addendum to the report (MAiD ethics in Quebec: reflections on a decade of deliberations) by Eugene Bereza and Véronique Fraser, also addresses the issue of socio-economic factors contributing to suffering. “Is it ethically acceptable that poverty, social isolation, refusal to go to a CHSLD or lack of access to care are factors that contribute significantly to a person’s subjective experience of intolerable suffering and lead to a request for MAiD?” (p. 122). LWD shares their concerns.

Large variations

between the 32 institutions remain unexplained

“Variation from single to triple in institutions for palliative and end-of-life care rates and MAiD…” For continuous palliative sedation (CPS), there is a variation from single to quintuple” (p. 112).

According to the Commission, “We must refrain from drawing hasty conclusions about institutions based on variations in the rate of the three end-of-life care services. There is nothing in this report to suggest inter-regional or inter-institutional inequity.” It adds that “where there is more palliative and end-of-life care, there is also more CPS and more MAiD.”

As we pointed out in our first press release, we know very little about the type of palliative care offered (there is a significant difference between a purely pharmacological approach in the later stages vs. comprehensive palliative care earlier on).

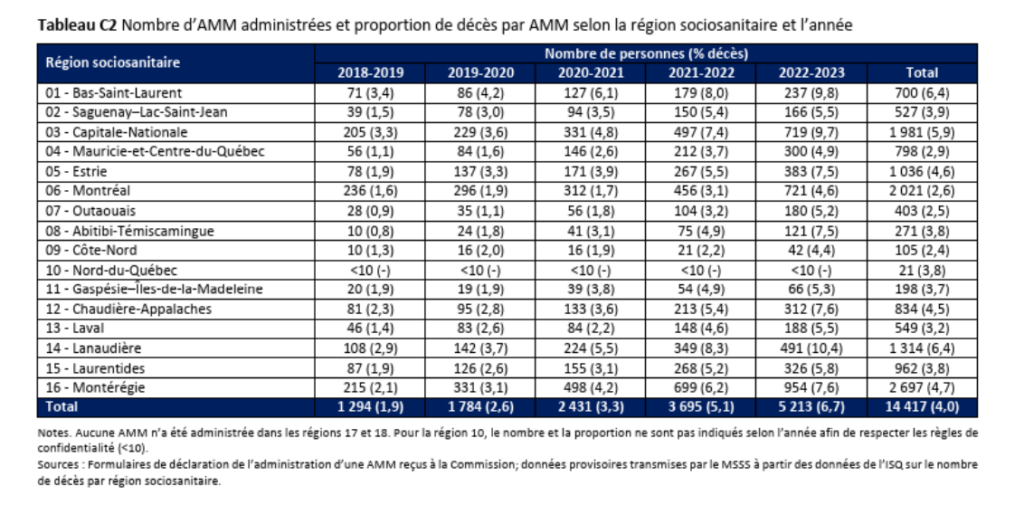

Through its network of health professionals, LWD believes that Quebec’s “continuum of care” approach is detrimental to the development of palliative care. Variations, such as rates of access to medical aid in dying ranging from 10.4% (Lanaudière), 9.7% (Quebec), 7.5% (Eastern Townships), 5.2% (Outaouais) to 4.6% (Montreal) in 2022-2023 (see Table C2), should make us reflect on access to end-of-life services across the province. Like the Commission, we hope that the work of the Consortium interdisciplinaire de recherche sur l’aide médicale à mourir (CIRAMM) will contribute to this.

– 30 –

Media contact :

Jasmin Lemieux-Lefebvre

Coordinator, Living with Dignity citizen network

www.vivredignite.org/en

info@vivredignite.org

438 931-1233

MAR

2025